Learn more about the history of the National Library of Medicine

-

Extraordinary Objects, Extraordinary Stories: Celebrating the NLM Collections, 1996

Historical Treasures of the National Library of Medicine, 1985 (pdf)

200 Years of American Medicine (1776–1976), 1976 (pamphlet) (pdf)

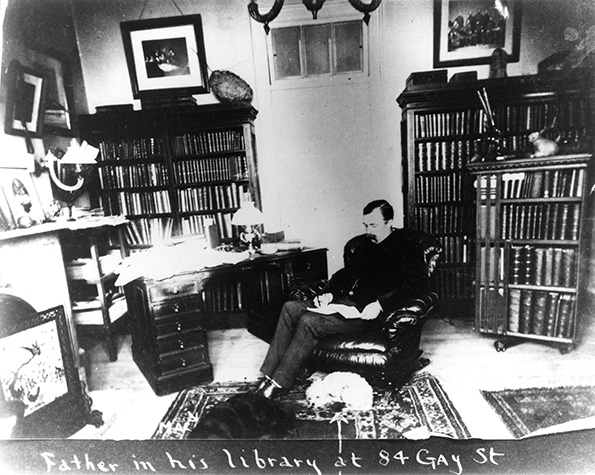

John Shaw Billings: An Autobiographical Fragment, 1965 (pdf)

John Shaw Billings Centennial, 1965 (pdf)

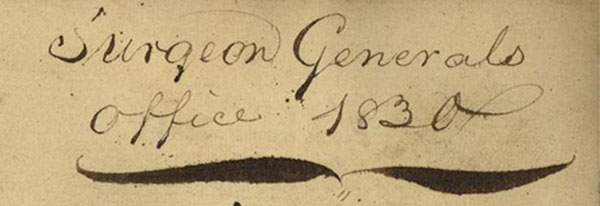

The First Catalogue of the Library of the Surgeon General’s Office Washington, 1840 (pamphlet) (pdf)

Close Close All Open All -

“Billings and Before: Nineteenth Century Medical Bibliography,” (pdf) in John B. Blake (ed.) Centenary of Index Medicus 1879–1979, (p. 31-52) U.S. DHHS, Public Health Service, NIH Publication No. 80-2068, 1980.

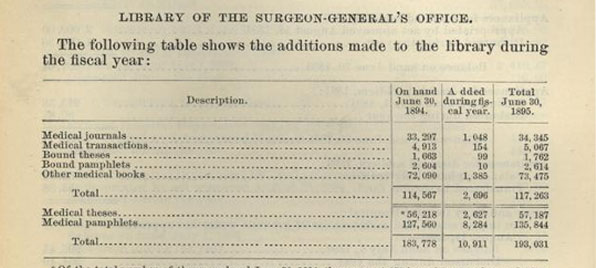

“From Surgeon General’s Bookshelf to National Library of Medicine: A Brief History,” by John B. Blake. Bull. Med. Libr. Assoc. 74 (4) October 1986, (p. 318-324).

“The Early Development of Medical Libraries in America,” by John Parascandola in Past, Present, and Future of Biomedical Information, (p. 5-15) U.S. DHHS, Public Health Service, NIH Publication No. 88-2911, 1987.

“The Old Library in Washington, 1836–1961,” by Frank Bradway Rogers in Past, Present, and Future of Biomedical Information, (p.16-26) U.S. DHHS, Public Health Service, NIH Publication No. 88-2911, 1987.

Close Close All Open All -

Images of America: US National Library of Medicine by Reznick, Jeffrey S. and Kenneth M. Koyle, with staff of the US National Library of Medicine, Mount Pleasant, South Carolina: Arcadia Publishing, 2017.

Hidden Treasure: 175 Years of the National Library of Medicineby Michael Sappol (ed.), New York: Blast Books, 2011.

A History of the National Library of Medicine: The Nation’s Treasury of Medical Knowledge by Wyndham D. Miles, Bethesda, Md. : U.S. Dept. of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, National Institutes of Health, National Library of Medicine, 1982.

Close Close All Open All