Many of the first PA students had served as U.S. Navy Hospital corpsmen in the Vietnam War, where they gained extensive practical experience in medicine and surgery before entering PA programs. As the profession grew, more programs such as Med-ical Ex-tenders (MEDEX) opened, and civilians, women, college graduates, and other under-represented groups increasingly entered the field.

Today, the profession encourages people from various backgrounds to become PAs. Programs like Project Access provide potential PA students from underrepresented groups with mentors who support their interest in the occupation. PA programs teach students how to identify their own biases and how to interact with colleagues and patients of different backgrounds, throughout the United States and beyond.

PA students at Touro College School of Health Sciences practice patient examinations together, New York City, 2009

Courtesy Touro College School of Health Sciences

Instructor Henry Armstrong(left) teaches PA student Luis Quijano (right) clinical chemistry during a class at the Charles Drew Postgraduate School of Medicine, Los Angeles, 1972

Courtesy National Library of Medicine

Named for a famous African American physician, the Charles Drew Postgraduate School of Medicine supports minorities who want to enter the health care field.

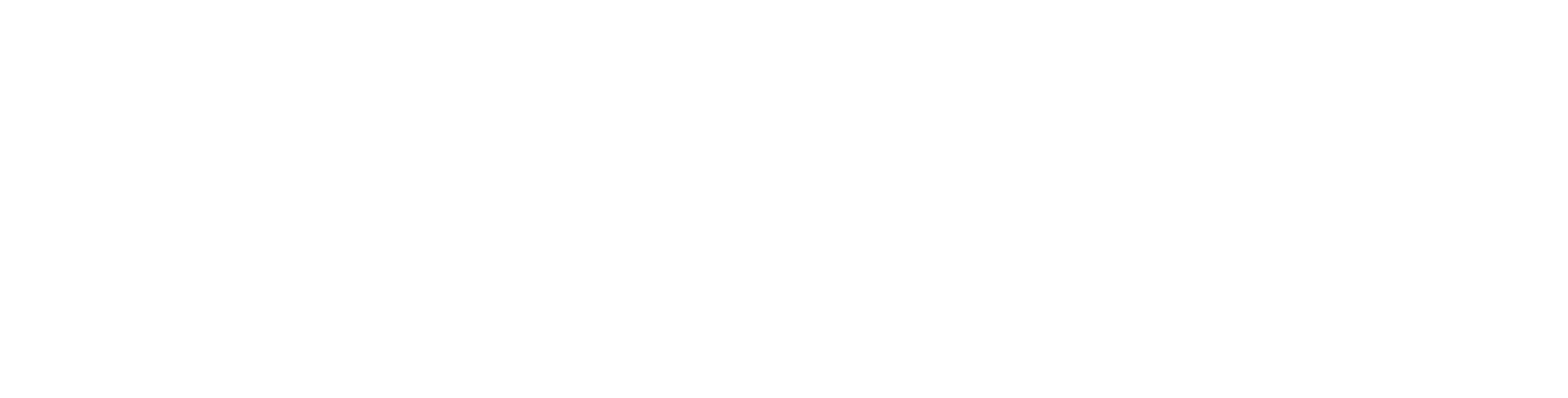

At the School of Allied Health Sciences, University of Texas Medical Branch, Kathy Lester (left) practices taking a patient’s blood pressure during her clinical training, Galveston, TX, 1972

Courtesy National Library of Medicine

The PA profession began as exclusively male, however, women increasingly enrolled in PA studies programs. In 1974 women made up 16% of the profession, and by 2014 the number had reached nearly 67%.

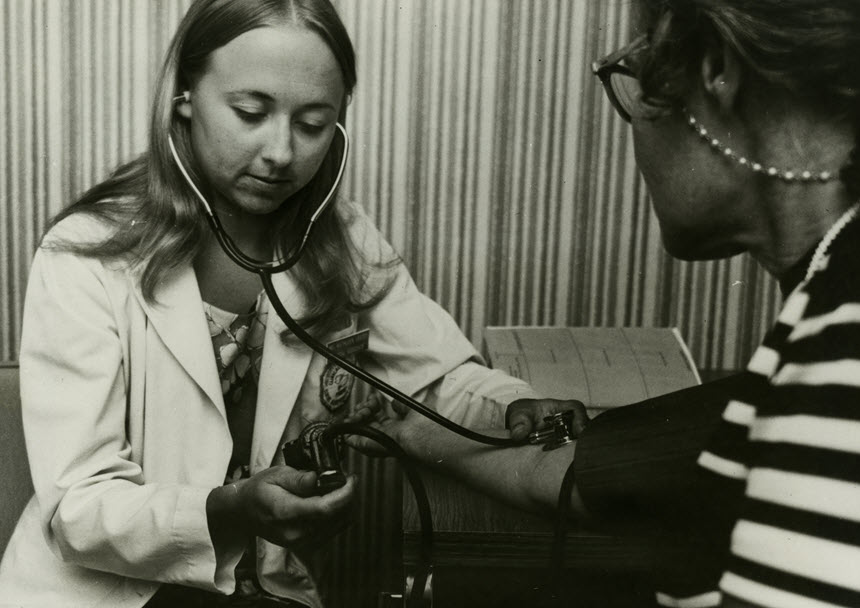

Joyce Nichols, PA-C (center) and aide Shirley Thompson (right) treat Raymond Hayes at the Lincoln Community Health Center’s foot clinic, Durham, NC, 1983

Courtesy University of North Carolina Archives

Growing up on a tobacco farm in rural North Carolina, Nichols overcame challenges to become the first female PA. Due to her background, Nichols devoted her career to aiding underserved rural, poor, and African American people. For example, she independently established a foot clinic at the historically African American Lincoln Community Health Center.

PA Shehla Ahmed (left) and PA Rubeena Zafar (right) work at the Hôtel-Dieu Grace Hospital in Windsor, Canada, 2008

Courtesy The Windsor Star

The Ontario government developed a two-year pilot program to train PAs and introduce the profession to the health care system. It attracted highly qualified foreign-trained medical graduates, like Ahmed and Zafar who emigrated from Pakistan and needed practical experience in Canada. The women’s cultural and ethnic backgrounds aided their practice by making patients in the community feel comfortable.

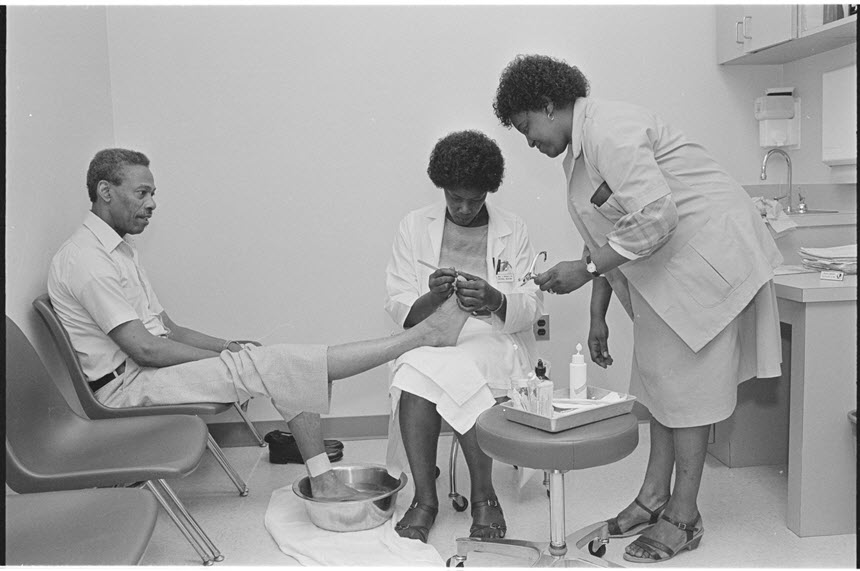

At the annual American Association of Physician Assistants conference, students from Howard University promote the school’s PA studies program, Washington, DC, 1982

Courtesy Physician Assistant History Society

Historically Black Colleges and Universities began opening PA studies programs soon after the birth of the profession. Howard created its program in 1973.

Mentor J. Curtis Vaughn, PA-C teaches YMCA campers how to use a reflex hammer at a Project Access event, Atlanta, GA, 2010

Courtesy American Academy of Physician Assistants

Students from Bruce Guadalupe Middle School learn how to use a stethoscope on PA students from Carroll University, Milwaukee, WI, 2015

Courtesy Carroll University

Cultural understanding is an essential part of Carroll University’s PA studies program. Students are required to evaluate their own identities and are exposed to many different cultures. During the program, PA students speak with underserved middle school students to expose them to jobs in science, engineering, and math.

PA students at Touro College School of Health Sciences practice patient examinations together, New York City, 2009

Courtesy Touro College School of Health Sciences

Instructor Henry Armstrong(left) teaches PA student Luis Quijano (right) clinical chemistry during a class at the Charles Drew Postgraduate School of Medicine, Los Angeles, 1972

Courtesy National Library of Medicine

Named for a famous African American physician, the Charles Drew Postgraduate School of Medicine supports minorities who want to enter the health care field.

At the School of Allied Health Sciences, University of Texas Medical Branch, Kathy Lester (left) practices taking a patient’s blood pressure during her clinical training, Galveston, TX, 1972

Courtesy National Library of Medicine

The PA profession began as exclusively male, however, women increasingly enrolled in PA studies programs. In 1974 women made up 16% of the profession, and by 2014 the number had reached nearly 67%.

Joyce Nichols, PA-C (center) and aide Shirley Thompson (right) treat Raymond Hayes at the Lincoln Community Health Center’s foot clinic, Durham, NC, 1983

Courtesy University of North Carolina Archives

Growing up on a tobacco farm in rural North Carolina, Nichols overcame challenges to become the first female PA. Due to her background, Nichols devoted her career to aiding underserved rural, poor, and African American people. For example, she independently established a foot clinic at the historically African American Lincoln Community Health Center.

PA Shehla Ahmed (left) and PA Rubeena Zafar (right) work at the Hôtel-Dieu Grace Hospital in Windsor, Canada, 2008

Courtesy The Windsor Star

The Ontario government developed a two-year pilot program to train PAs and introduce the profession to the health care system. It attracted highly qualified foreign-trained medical graduates, like Ahmed and Zafar who emigrated from Pakistan and needed practical experience in Canada. The women’s cultural and ethnic backgrounds aided their practice by making patients in the community feel comfortable.

At the annual American Association of Physician Assistants conference, students from Howard University promote the school’s PA studies program, Washington, DC, 1982

Courtesy Physician Assistant History Society

Historically Black Colleges and Universities began opening PA studies programs soon after the birth of the profession. Howard created its program in 1973.

Mentor J. Curtis Vaughn, PA-C teaches YMCA campers how to use a reflex hammer at a Project Access event, Atlanta, GA, 2010

Courtesy American Academy of Physician Assistants

Students from Bruce Guadalupe Middle School learn how to use a stethoscope on PA students from Carroll University, Milwaukee, WI, 2015

Courtesy Carroll University

Cultural understanding is an essential part of Carroll University’s PA studies program. Students are required to evaluate their own identities and are exposed to many different cultures. During the program, PA students speak with underserved middle school students to expose them to jobs in science, engineering, and math.

Many of the first PA students had served as U.S. Navy Hospital corpsmen in the Vietnam War, where they gained extensive practical experience in medicine and surgery before entering PA programs. As the profession grew, more programs such as Med-ical Ex-tenders (MEDEX) opened, and civilians, women, college graduates, and other under-represented groups increasingly entered the field.

Today, the profession encourages people from various backgrounds to become PAs. Programs like Project Access provide potential PA students from underrepresented groups with mentors who support their interest in the occupation. PA programs teach students how to identify their own biases and how to interact with colleagues and patients of different backgrounds, throughout the United States and beyond.