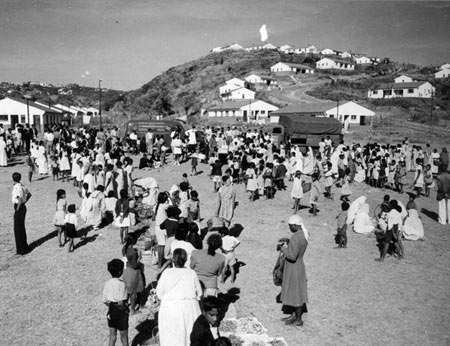

In 1942, Sidney and Emily Kark founded a health center in Pholela, an impoverished Zulu tribal reserve in the eastern province of Natal, South Africa. Because they recognized that poverty played a key role in the health problems in the region, the doctors expanded their medical work to include improving housing, sanitation, and access to food. Their innovative approach inspired other projects around the world and helped shape the first community health centers in the United States.

A patient receiving a vaccination, Pholela, early 1940s Courtesy Jeremy D. Kark, M.D., Ph.D.

Medical students in the dissecting room at the University of Natal, 1950s

Medical students in the dissecting room at the University of Natal, 1950sCourtesy Rockefeller Archive Center

In 1946, Sidney Kark established the Institute of Family and Community Health, a training program linked to a community health center in Durban, South Africa. The institute became

part of the Department of Social, Preventive and Family Medicine at the University of Natal a few years later.

Dr. Kark introduced a curriculum based on his concept of "social medicine." This comprehensive approach to health care included epidemiology, population health assessment, health

administration, community nursing, health education, environmental sanitation, laboratory services, and nutrition.

Letter from Sidney Kark to the principal of the University of Natal, 1957

Letter from Sidney Kark to the principal of the University of Natal, 1957Courtesy The Rockefeller Foundation

The University of Natal opened the first medical school to train non-white students in South Africa in 1947. A year later, the government introduced apartheid, (literally "separateness"

in Afrikaans), a legal system of racial segregation enforced from 1948 to 1994.

The faculty frequently clashed with the government over apartheid. On March 11, 1957 a government minister introduced a bill to seize control of the medical school. Sidney Kark wrote a letter to

the university's principal criticizing the plans and resigned in response to the growing constraints on his work.

Sidney and Emily Kark (center) with colleagues, Jerusalem, 1960s

Sidney and Emily Kark (center) with colleagues, Jerusalem, 1960sCourtesy Jeremy D. Kark, M.D., Ph.D.

After leaving South Africa to escape harassment and surveillance under the apartheid regime, Dr. Sidney Kark and his wife Emily brought their ideas to the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill. In 1959

they moved to Jerusalem, where they created a health center and "social medicine" program at the Hadassah-Hebrew Medical School.

"You had to live near the health center so that you could see the role models, the African health workers and medical students…"—

Nkosazana Dlamini Zuma, 1988

Beginning in the early 1990s, after years of demonstrations and diplomatic pressure from abroad, political leaders in South Africa were forced to dismantle apartheid. On May 10, 1994, Nelson Mandela was elected

South Africa's first black president in the country's democratic election.

Dr. Nkosazana Dlamini Zuma, who decided on a career in medicine while growing up in Pholela, was appointed minister of health in President Mandela's government. During the country's rule by the predominantly white

Afrikaaner party, the Pholela Health Center had been shut down. In 2001, Dr. Zuma oversaw the launch of a new clinic there as part of the rebuilding of South Africa's health services.