ACTION ON AIDS

|

FIGHTING DISCRIMINATION

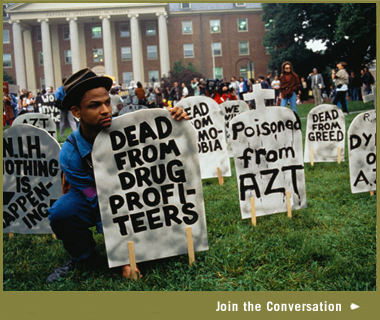

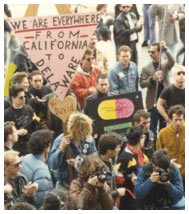

ACT UP protest at the National Institutes of Health, 1990 Courtesy Donna Binder

"It is time to put self-defeating attitudes aside and recognize that we are fighting a disease—not people."—Surgeon General C. Everett Koop, 1986

In 1986, five years after AIDS was first reported and with more than ten thousand people in the United States thought to have died from the disease, President Reagan acknowledged the epidemic by

asking Surgeon General C. Everett Koop to prepare a report. Dr. Koop surprised both his supporters and critics by his straightforward approach and frank endorsement of condoms and sex education as

ways to prevent the spread of the disease.

CHALLENGING INEQUALITY:

Dr. Jack Geiger remembers the early years of the Delta Health Center.

TranscriptTAKING QUESTIONS:

Watch President Reagan answer questions on AIDS publicly for the first time, September 17, 1985.

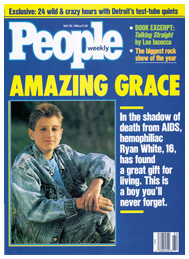

TranscriptIn 1985, Ryan White, a 13-year-old hemophiliac with AIDS, was barred from attending school on the grounds that he might transmit HIV to other students. Although he eventually won a court

battle to return to classes, Ryan and his family experienced ongoing intimidation and harassment. They moved from Howard County to Cicero, Indiana in 1987, where Ryan became an honor-roll student.

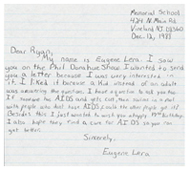

Letter from 11-year-old Eugene Lera to Ryan White, 1988

Letter from 11-year-old Eugene Lera to Ryan White, 1988Courtesy The Children's Museum of Indianapolis

Ryan White educated people about the facts of the disease and advocated for the rights of people living with AIDS. In 1988, in one of many letters children and adults around the world sent to Ryan,

Eugene Lera of Vineland, New Jersey, wrote to ask a question and express his hope for a cure.

The media coverage of Ryan White's experiences exposed the discrimination experienced by people living with HIV and AIDS. He was interviewed on numerous television stations and appeared on the cover

of People magazine twice before his death in 1990. His story helped many people become more sympathetic towards people living with the disease.

ACT UP starts up

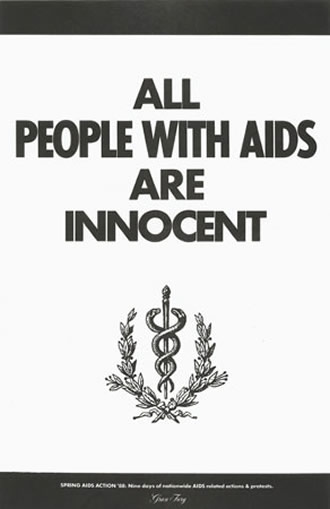

"All People With AIDS Are Innocent"—ACT UP slogan, 1980s

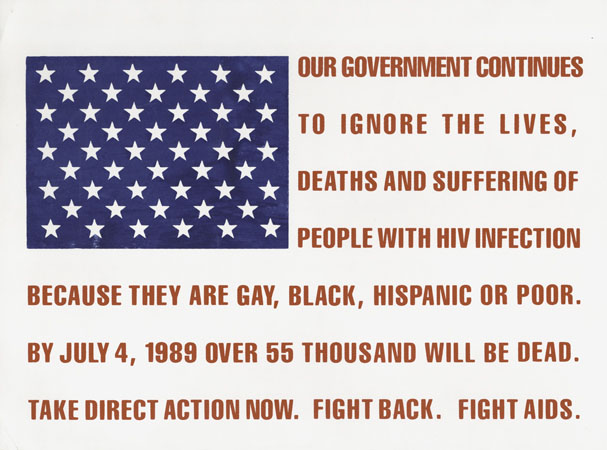

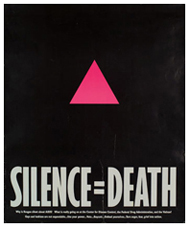

AIDS activism poster by the Silence = Death Project, 1986

AIDS activism poster by the Silence = Death Project, 1986Courtesy International Gay Information Center Collection. Manuscripts and Archives Division, The New York Public Library, Astor, Lenox and Tilden Foundations

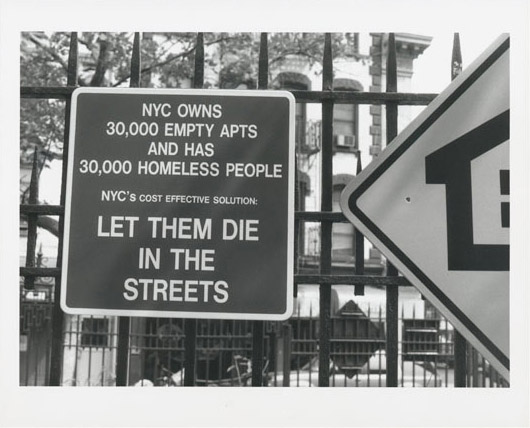

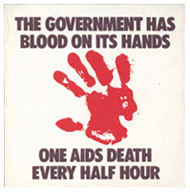

In New York in 1987, about three hundred people formed the AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power (ACT UP), to challenge discrimination against people living with AIDS. They launched a series

of provocative demonstrations to campaign for AIDS research and HIV prevention education. The slogan Silence = Death, developed by an activist art collective later known as Gran Fury, appeared with the inverted

pink triangle, a symbol of gay rights, on many of the group's posters and placards.

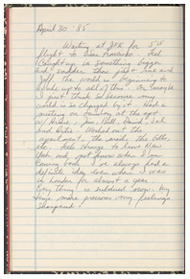

Vito Russo's diary, 1980s

Vito Russo's diary, 1980sCourtesy Vito Russo papers. Manuscripts and Archives Division, The New York Public Library, Astor, Lenox and Tilden Foundations

In 1985, shortly after Vito Russo's partner Jeffrey Sevcik was diagnosed with AIDS, Russo expressed his profound sadness at the slow recognition of the true scale of the epidemic: "The world is beginning to wake up to all of this." Both men died from the disease and are remembered in panels of The AIDS Memorial Quilt.

Vito Russo, an author, film critic, and one of the founding members of the AIDS activist group ACT UP, wrote about the early years of AIDS in his diary. He described the lack of media

coverage, and the fears and outrage of his friends as they saw their loved ones fall ill.

ACT UP Women's Committee

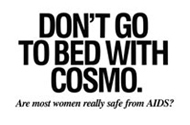

When Cosmopolitan magazine published "Reassuring News about AIDS," an article by Dr. Robert Gould claiming that heterosexual women did not need to worry about contracting HIV, a group of women within ACT UP

organized a protest.

They gathered outside the New York offices of the magazine's publisher and met with the author to discuss the evidence for heterosexual transmission of the virus.

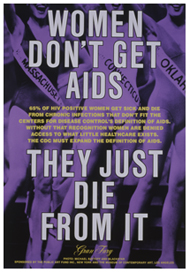

AIDS activism poster by Gran Fury, 1991

AIDS activism poster by Gran Fury, 1991Courtesy Gran Fury Collection. Manuscripts and Archives Division, The New York Public Library, Astor, Lenox and Tilden Foundations

Although women are at risk of contracting HIV through heterosexual sex, in the early years of the epidemic the definition of AIDS proposed by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) was based on

the symptoms most frequently experienced by men. As a result of protests by ACT UP, the CDC expanded its definition to include the most common symptoms among women with the disease.

ACT UP and the FDA

ACT UP demonstration at the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA), October 11, 1988

ACT UP demonstration at the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA), October 11, 1988Courtesy Food and Drug Administration History Office

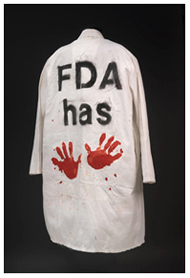

On October 11, 1988 ACT UP closed down the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) outside Washington, DC, to protest the slow process of drug approval. They argued that because there were few treatments for AIDS, new drugs

should be reviewed as quickly as possible. The FDA streamlined the review process for key AIDS medications including AZT, and within a few years introduced rules to fast-track approval for drugs that could save lives.

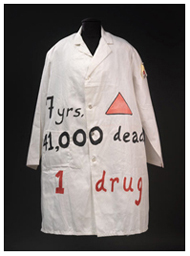

Lab coat worn by ACT UP member Mark Carson at the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA), October 11, 1988

Lab coat worn by ACT UP member Mark Carson at the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA), October 11, 1988Courtesy ACT UP New York Records. Manuscripts and Archives Division, The New York Public Library, Astor, Lenox and Tilden Foundations

One of the reasons for the success of ACT UP protests was the media attention their activities received. The use of costumes, placards, and dramatic slogans clearly and memorably conveyed their message and focused the public's attention on specific issues, like drug development and approval, which shaped the AIDS crisis.

One of the reasons for the success of ACT UP protests was the media attention their activities received. The use of costumes, placards, and dramatic slogans clearly and memorably conveyed their message and focused the public's attention on specific issues, like drug development and approval, which shaped the AIDS crisis.